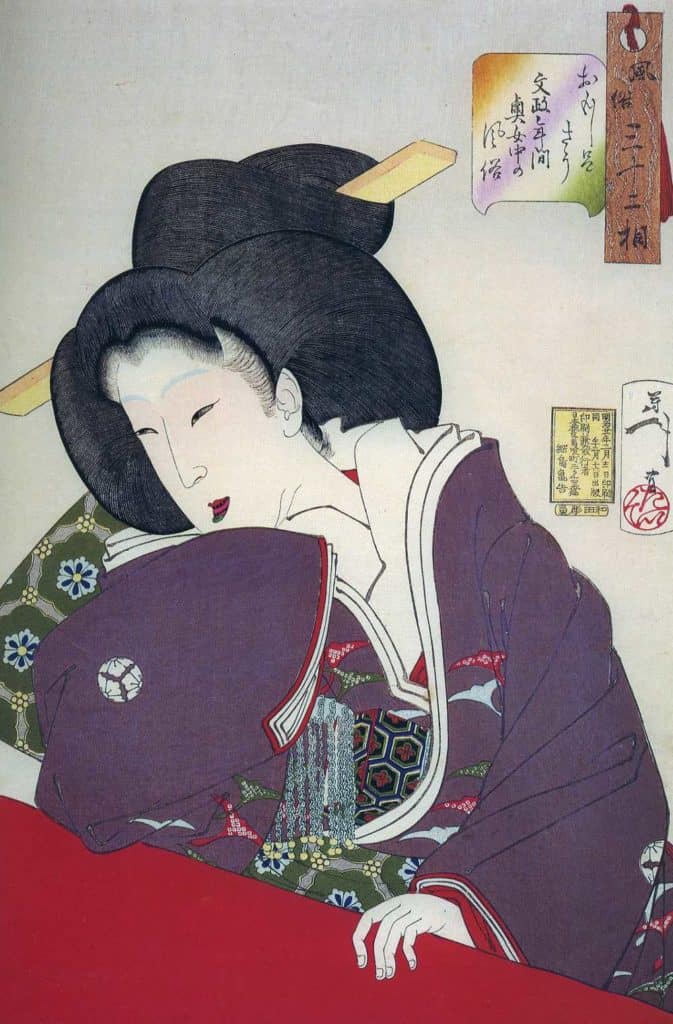

‘The tayu knelt next to me, adjusting her skirts. Underneath it all she had a cheeky, elfin face with a tiny nose and pointed chin. How long had she been a tayu, I asked, then gasped when she opened her small mouth to answer. In the chalky-white face with the blood-red lips, her teeth were painted black. It was macabre, like looking into a black hole.’ (Geisha: The Secret History of a Vanishing World by Lesley Downer, Headline 2000)

When Commodore Perry arrived in Japan on July 8th 1853, he probably didn’t meet any women at all, though he may have seen the odd commoner peeping out from behind a barrier to catch a glimpse of the monstrous new arrivals. But if he had, he would have seen that all married women had black teeth – in fact not just women but aristocrats and courtiers too.

When a woman set about her toilette, her first job was to shave her eyebrows and freshen up the blacking on her teeth. To Japanese eyes black teeth were beautiful, like shiny black lacquerware, smooth and perfect and blemish free. Black teeth were a mark of sexual maturity and all women, from samurai to farmers, blackened their teeth the moment they got married. White teeth looked positively barbaric.

To blacken their teeth women used a dye of sumac-leaf gall, sake and iron. To make it you soaked pieces of iron in tea or vinegar, giving a rust coloured liquid, then added tannin in the form of powdered sumac leaf gall to turn it black. Then you painted it on warm, tooth by tooth, with a soft feather brush.

It usually needed several applications and had to be topped up every few days to maintain a perfect glossy sheen, like nail polish.

At the time women wore chalky white make up. At night, by candlelight, as in the case of geisha, a woman’s face glimmered magically. Unpainted teeth would have looked unpleasantly yellow in contrast and the black lacquer helped hide the teeth, which may not have been in the best of shape.

Black teeth were simply the norm. In the 12th century Tsutsumi Chunagon Monogatari there’s a story about an eccentric young woman who loved insects. So eccentric was she that ‘she would not pluck a single hair from her eyebrows nor would she blacken her teeth, saying it was a dirty and disagreeable custom.’ One day a handsome Captain happened to pass by by and admired her from a distance. But then she smiled and he saw her unblackened teeth gleaming and flashing and was quite disgusted. ‘There was something wild and barbaric about it.’

When the British diplomat Ernest Satow arrived in Japan in 1861 at the age of 18, he sneaked off to an out of bounds geisha house in Osaka one day, having heard all about the wonderful geisha. But he had a nasty shock. The women were certainly pretty but he hadn’t expected black teeth and white lead-painted faces.

And it wasn’t just women. When Algernon Mitford, another British diplomat and the grandfather of the famous Mitford sisters, met the 16-year-old Emperor Meiji in 1868, the emperor had shaved eyebrows, rouged cheeks and black teeth.

But in the end both men became so used to the practice that when Empress Haruko declared in 1873 that she would no longer blacken her teeth they found it every bit as shocking as the Japanese did. Ernest Satow wrote of how strange it was to see ladies with white teeth.

If you think about it teeth-blackening was no more extraordinary than any of the ways we adorn ourselves – from Elizabeth I covering her face in poisonous white lead make up, to women teasing their hair into massive beehives in the Sixties, or people getting tattoos or piercings today. Plus the lacquer helped prevent tooth decay and enamel decay. It was probably no worse for you than teeth whitening gel. It’s all a question of adjusting the lens through which you see the world.

Fascinating read Lesley although I’m not sure I’d fancy it now.

Thank you for all the fascinating detail in this. I noticed when in Japan last month that hotel and spa baths did not admit people with tattoos, I think because they’re associated with gangs and seen as intimidating.