One bitter December day in 1868, 3000 Japanese warriors sailed into Hakodate Bay, on the tip of the northern island of Ezo (now Hokkaido), close to the Japanese mainland. Their ambition was to defeat the imperial forces and set up a republic loyal to the deposed shogun. But when spring came the imperial government sent an army of 10,000 men with a ship far more modern and formidable than those the rebels had. Huge battles were fought on sea and land but eventually the rebels were defeated. Even among Japanese their story is largely forgotten.

One bitter December day in 1868, 3000 Japanese warriors sailed into Hakodate Bay, on the tip of the northern island of Ezo (now Hokkaido), close to the Japanese mainland. Their ambition was to defeat the imperial forces and set up a republic loyal to the deposed shogun. But when spring came the imperial government sent an army of 10,000 men with a ship far more modern and formidable than those the rebels had. Huge battles were fought on sea and land but eventually the rebels were defeated. Even among Japanese their story is largely forgotten.

One hundred and forty years later, I arrive in Hakodate to see if anything remains of their last desperate attempt to stem the tide of history. Hakodate is famous for its wild weather but I am not prepared for the blizzard that coats me in snow in the minutes it takes to walk from the tram stop to my hotel.

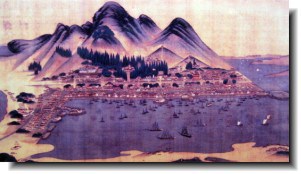

Hakodate spreads picturesquely around the foothills of Mount Hakodate. There’s a cable car to the top from where you can look down on the city, spreading in an hourglass shape across the peninsula, and on the lights of boats fishing for squid. Locals claim it is one of the three best night-time views in the world, on a par with Naples and Hong Kong.

According to many seafarers, including Commodore Matthew Perry who sailed in in 1854, Hakodate Bay is one of the best natural harbours in the world, deep enough for large ships to anchor close to shore and enclosed by land, keeping the water calm and peaceful. It’s a very beautiful place. With its steep hills plunging down to the blue waters of the bay, the city is reminiscent of San Francisco. And the fact it’s a perfect harbour has determined its fate.

Back in the mid nineteenth century it was one of the first three places in Japan where westerners were allowed to settle. British, Americans and Russians soon arrived, among them the British adventurer Thomas Blakiston who started a lumber business in 1861 and ran guns to the rebels.

The city grew into a thriving international community. Many splendid old buildings are still there to attest to it. I climb through deep snow to admire the Old British Consulate, built in 1859. A picture book confection in cream and blue with a Narnia lamppost outside and icicles hanging from the eaves, it still serves Victorian cream teas. Perched on the hillside above it is the spectacular Old Public Hall from which the colony was governed, a vast rambling yellow and white wooden building with verandas and porches out of ‘Gone with the Wind’. An icy road leads to the the onion-domed Russian Orthodox Church, established in 1861, and the nearby Roman Catholic Church. There is also a Trappist Convent a little way out of town, founded by eight French nuns in 1868. One wonders what they were doing so far from home.

The city grew into a thriving international community. Many splendid old buildings are still there to attest to it. I climb through deep snow to admire the Old British Consulate, built in 1859. A picture book confection in cream and blue with a Narnia lamppost outside and icicles hanging from the eaves, it still serves Victorian cream teas. Perched on the hillside above it is the spectacular Old Public Hall from which the colony was governed, a vast rambling yellow and white wooden building with verandas and porches out of ‘Gone with the Wind’. An icy road leads to the the onion-domed Russian Orthodox Church, established in 1861, and the nearby Roman Catholic Church. There is also a Trappist Convent a little way out of town, founded by eight French nuns in 1868. One wonders what they were doing so far from home.

The oldest western building in the city, a grey stone edifice, houses the splendid Museum of Northern Peoples. Long before Japanese or western settlers arrived, the original inhabitants of the island were the Ainu, a people akin to the Inuit, who lived on fish, sea otter and seals. In the eighteenth century the shogun’s government, aware that Ezo formed a bulwark against Russia to the north, sent explorers to report on them. The museum displays the explorers’ paintings depicting Ainu lifestyle and customs, along with seal-skin kayaks, fur-covered caps and boots, amulets and sleds.

The 3000 warriors headed not for Mount Hakodate but inland, to the city’s famous fortress, the Goryokaku. They captured it and made it their headquarters. A five-sided fort built on the French model in 1864, it was the first western-style fortress in Japan. Its hefty stone ramparts and surrounding moat form a perfect star, an extraordinary and beautiful sight. In the grounds there is a museum displaying the men’s uniforms, with braided cuffs and collars but fastened with ties, not buttons. Their helmets are conical like traffic cones or shaped like conch shells.

The 3000 warriors headed not for Mount Hakodate but inland, to the city’s famous fortress, the Goryokaku. They captured it and made it their headquarters. A five-sided fort built on the French model in 1864, it was the first western-style fortress in Japan. Its hefty stone ramparts and surrounding moat form a perfect star, an extraordinary and beautiful sight. In the grounds there is a museum displaying the men’s uniforms, with braided cuffs and collars but fastened with ties, not buttons. Their helmets are conical like traffic cones or shaped like conch shells.

I was thrilled to discover that there is something left of these adventurers over and above the spectacular five-sided fortress and a few stones marking their graves. Before civil war broke out, the shogun sent fifteen youths to Holland to study naval affairs. They commissioned a state-of-the-art sailing-cum-steam ship, the Kaiyo Maru, and sailed it back by way of Rio and Batavia (now Jakarta), a journey of 150 days. When they fled north, they took it as the flagship of their navy. But in a huge typhoon on the other side of the peninsula it sank, a dreadful portent.

Almost a hundred years later, divers salvaged it. They brought up masts, funnels, lifeboats, cannons, cannon balls, rifles and the entire effects of one Kamekichi, whose name tag was also found – his straw sandals, fan, tweezers, comb, coin box and wooden rice dish. With its two funnels and three masts, the Kaiyo Maru now stands proudly in the harbour across the peninsula from Hakodate.

In the evening talk, laughter, smoke and succulent smells seep from the closed doors and steamed up windows of rows of tiny yatai restaurants. I squash in along a counter beside three office workers while the lady of the house grills up squid (a local speciality) and Hokkaido salmon.

I discover that while the rebels may be forgotten in the rest of the country, they’re not forgotten here. Toshizo Hijikata, the swashbuckling leader of the shogun’s crack military corps, became a local legend. Well aware that their cause was hopeless, he composed a death poem which reads, ‘Though my body may decay on the island of Ezo, My spirit guards my lord in the east.’ He was gunned down on the battlefield aged thirty four. There are statues of him in Hakodate and a shrine to mark the spot where he fell.

I discover that while the rebels may be forgotten in the rest of the country, they’re not forgotten here. Toshizo Hijikata, the swashbuckling leader of the shogun’s crack military corps, became a local legend. Well aware that their cause was hopeless, he composed a death poem which reads, ‘Though my body may decay on the island of Ezo, My spirit guards my lord in the east.’ He was gunned down on the battlefield aged thirty four. There are statues of him in Hakodate and a shrine to mark the spot where he fell.

Why is he such a hero here, I ask. ‘Because he died for what he believed in,’ says one of my dining companions sagely. And that purity of purpose is what endears him to the Japanese.

Hakodate is rich with history. But the world long since moved on, leaving the city to its memories. These days it’s rarely visited. With its trams, its arcades playing piped music and its blustering sub-zero winds, it’s feels as if it’s stuck in a time warp.

Yet the thick crust of snow on roofs and roads, the fringes of icicles and icy winds driving in off the ocean give it a robust charm all its own. It feels like frontier country. It’s fresh, clean, hopeful, young, the sort of place where pioneers might come hoping to carve out a new life or a new country – as the 3000 rebel warriors did.

Lesley Downer’s latest book, The Last Concubine, was published by Bantam Press on February 14th 2008.

First published in the Financial Times, February 2nd, 2008