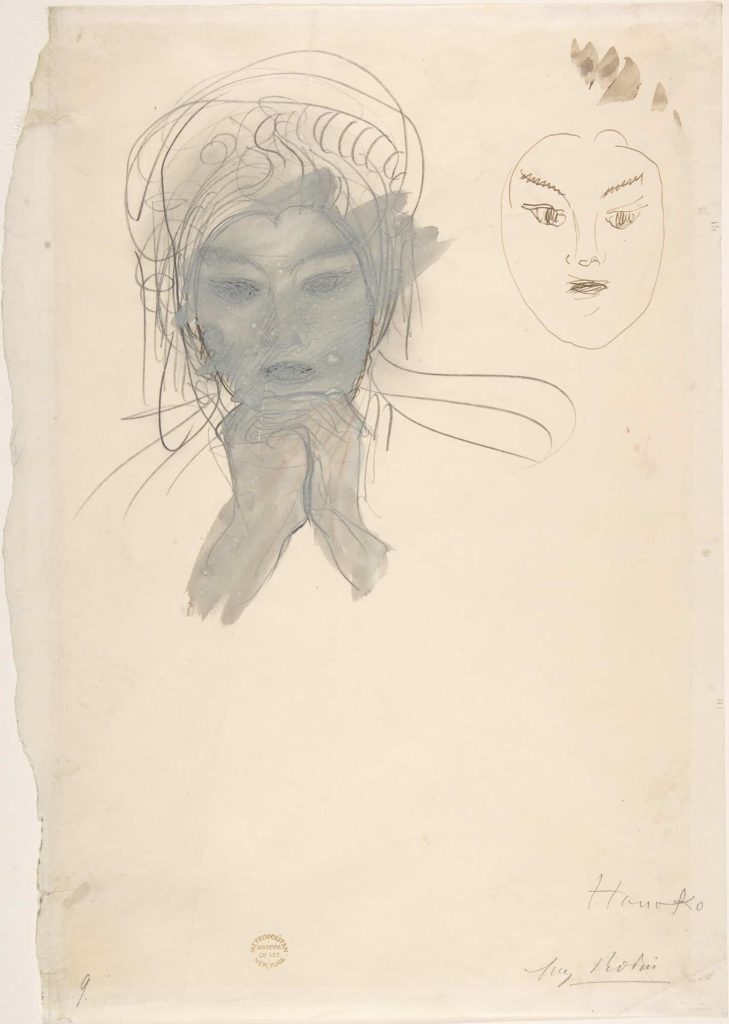

Metropolitan Museum of Art (public domain)

Some of the most intriguing of August Rodin’s works are the fifty three heads, masks and busts of the Japanese dancer Hanako he made late in life, several of which are currently on display at the Tate Modern exhibition The Making of Rodin. Some are calm and placid, but many are contorted in anguish or rage, forehead creased, lips clenched, eyes staring. They’re depictions not so much of a person as of an intense emotion.

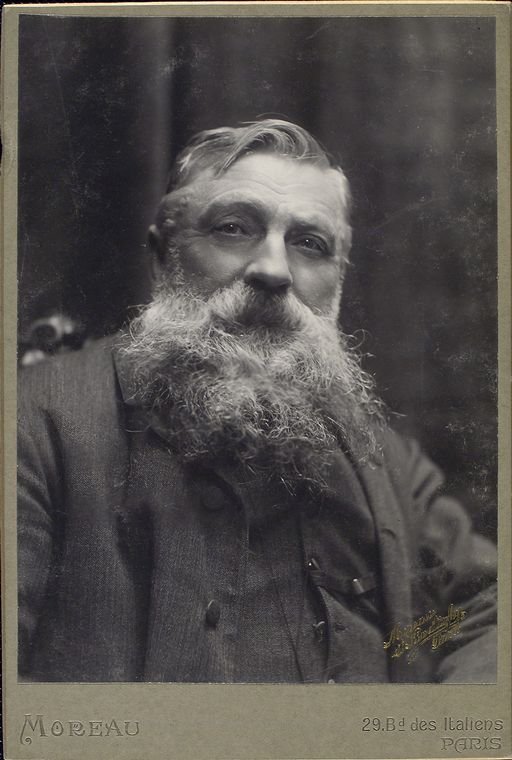

When Rodin met Hanako in 1906, he was 67 and hugely famous. A decade had passed since he’d created the last of his spectacular sculptures, Balzac. Now he seemed to have lost his edge.

But he was still obsessed with capturing the body in motion. He had gone to the Marseilles Colonial Exposition to sketch the Cambodian dancers who were performing. There he visited a small hut erected in the woods where a tiny Japanese dancer was performing a shockingly realistic death scene. This was Hanako. Rodin was transfixed.

After the performance he gave her his visiting card and told her to look him up in Paris. Thus began an association and a friendship that was to last for the rest of his life.

At the time Japanese art and artefacts were all the rage across Europe and America and most especially in Paris. Japonisme, as the craze was dubbed, transformed western visual arts, culture and design and inspired Art Nouveau among much else. The west was gripped by the delicacy and beauty of this mysterious culture.

Artists like Van Gogh, Monet, Manet and Toulouse Lautrec were inspired by the precision, line and extraordinary perspectives of Japanese woodblock prints. Fashionable women wore kimono and filled their homes with screens, fans, lacquerware, swords and blue and white porcelain. In London Arthur Lasenby Liberty opened his legendary shop on Regent Street, while in Paris Siegfried Bing purveyed Japanese goods from his shops in the Ninth Arondissement.

Rodin too was caught up in the craze, amassing woodblock prints and Japanese art objects to add to his collection of Greek, Roman and Egyptian antiques.

In 1899 the brilliant actress and dancer, Sadayakko, swept across America and Europe, performing at the White House, to sell-out audiences and before the Prince of Wales. Picasso painted her, Puccini modelled his Madama Butterfly on her, and Rodin asked her to sit for him but she said she had no time.

Finally she returned to Japan, leaving the west hungry for another Japanese star – and Hanako fit the bill.

Auguste Rodin – portrait middle aged

Tucker Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

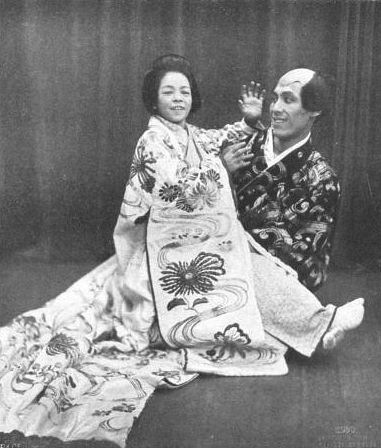

Hisa Ota (Hanako)

Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hanako – ‘Little Flower’ – was not quite what Parisians imagined her to be. She was born Ota Hisa into a provincial family in central Japan, trained as a geisha, then heard that Japanese dancers were wanted for an exposition in Copenhagen. She arrived there in 1902. She was 34 but at 4 foot 6 inches so tiny that Europeans took her to be much younger.

At first she didn’t find many engagements. But then Loie Fuller spotted her at London’s Savoy Theatre. Fuller, a flamboyant American dancer and impresario, had been the manageress of Sadayakko and of Isadora Duncan. In her memoir she wrote, Hanako ‘was suddenly able to transform herself with little movements which froze all the anguish of terror into her features. She was pretty, delicate, strange, and stood out even among her fellow countrymen.’ As for her death scene, ‘She was devastating.’

Lacking authentic Japanese plays, Fuller wrote them herself, ensuring that each play ended in ‘hara-kiri’ – not women’s ritual suicide, slitting one’s throat, but cutting open the belly which in reality only male samurai performed. Hanako performed it so vigorously that people in the front row were splashed with ‘blood’. It was completely inauthentic but French audiences loved it.

Rodin and Fuller were good friends. Rodin loved sketching dancers and Fuller’s undulating movements and swirling veils were a huge inspiration for him. At the Marseilles Colonial Exposition, Fuller took him to see Hanako perform. Nothing could deny the ‘flame which illuminated her from within.’ For him it was a new lease of life.

Omar David Sandoval Sida, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

National Gallery of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Auguste Rodin, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Back in Paris he invited her to lunch at his atelier and asked her to sit for him. He wanted to capture the same expression he’d seen at the Marseilles Expo. In payment he said that he would give her and Fuller each one of his works.

Each morning Fuller took her by car to his atelier. Hanako sat for about half an hour then he took them both to lunch. Sometimes she sat for another half hour in the afternoon, before going to the theatre to perform.

Years later, back in Japan, Hanako reported how difficult it was for her to hold this anguished expression, which was completely opposite to her normal cheerful disposition. From time to time she moved her eyes when they began to ache. ‘Fumbling the clay with his fingers, M. Rodin was very slow in his palette work. If I moved my eyeball a little, he instantly said, “Non, non. Attends, attends.” ’

Once she sat down to rest in the garden. Rodin grabbed a sketchbook and shouted at her not to move. In the end he spent every morning making ‘Head of Death’ and every afternoon working on ‘Meditating Woman,’ the placid face she had when she was resting.

‘When the mask was completed after such a long struggle he was highly delighted. Putting out all the lights in the room, he brought in some candles and put them around the mask. Then he called in Mme Rodin and we celebrated the completion of the mask.’

He also asked her to pose naked, a normal request for him. He liked to capture the play of muscles and ligaments. At first she refused but then Madame Rodin (Marie Rose Beuret, Rodin’s partner for 53 years) begged her too. He did several paintings of her resting on one leg with the other across it. He told a friend, ‘Hanako is so strong she could stand on one leg as long as she wanted.’

For the next twelve years, every summer ‘when the olive leaves began to brighten’, during the theatre off season, Hanako went to Rodin’s home in Val Fleury in Meudon in the Paris suburbs for three month’s vacation. She lived like a member of the family, with Lada, Rodin’s dog, sleeping in her room. Rodin gave her money if ‘he found [her] purse thin’ and showed her his many books of Japanese and Chinese art. In all he produced fifty three busts, masks and heads of Hanako, more than of any other sitter. There were even rumours that they were lovers.

Rodin died in 1917. Hanako visited his tomb the next year at Meudon and wept when his dog wagged its tail when it saw her. It was only after his death, when she was back in Japan, that she finally got the two busts she had been promised – ‘Head of Death’ and ‘A Meditating Woman’.