Ibusuki was a beautiful place, a land of gold and sunshine where the sky and ocean were perpetually blue. Cranes swooped, birds twittered, monkeys roamed the flower-clad hills, palm trees swayed and the purple cone of Mount Kaimon, more perfect than Mount Fuji, rose misty on the horizon …

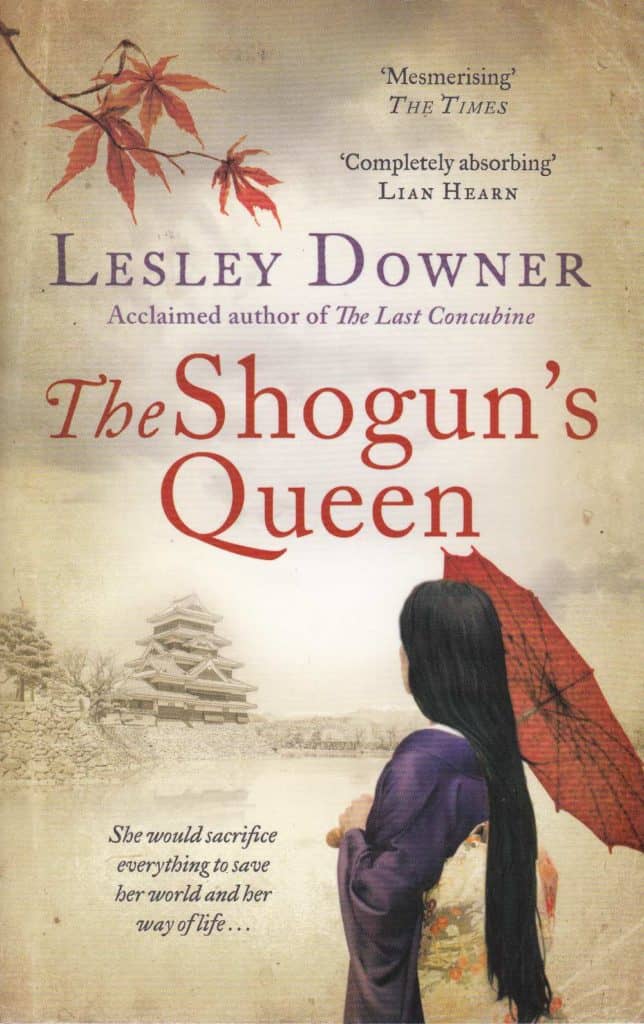

The Shogun’s Queen

For me researching a book always involves travel. Even when I’m writing fiction the sense of place is always crucial, perhaps because I began by writing travel books and am still a travel writer – or perhaps it’s that I just love travel.

Each book in The Shogun Quartet has taken me to very extraordinary, seldom visited, unexplored corners of Japan and enabled me to unearth different aspects of its history. The Last Concubine took me to the Nakasendo, the Inner Mountain Way that winds along the valleys of central Japan, and to Mount Akagi, where the shogun’s lost gold is said to be buried. (And no, I didn’t find it). For The Courtesan and the Samurai I went to Hakodate, on Japan’s northernmost island, Hokkaido, and got covered head to foot in snow while visiting the sites where the last great battle of Japan’s civil war was fought. I also fell in love with Victorian-era sail and steam ships. And The Samurai’s Daughter took me to the northern city of Aizu Wakamatsu very near Fukushima, not long after the terrible earthquake and tsunami.

My latest novel and the prequel to The Last Concubine, The Shogun’s Queen, is based very closely on fact. Princess Atsu’s story is so powerful I really wanted to bring her and the places which she knew alive.

By 名古屋太郎 (Own work PENTAX K10D + smc PENTAX-A 1:1.2 50mm) [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

Atsu grew up in the idyllic seaside and spa resort of Ibusuki and spent the first seventeen years of her life there. It’s a glorious tropical resort at the far tip of the southern island of Kyushu. Not far away you can see Mount Kaimon, a fairy-tale cone-shaped mountain even more perfect than Mount Fuji. People go there for their health, but instead of taking the waters you’re buried in hot black mineral sands. You put on a cotton gown called a yukata and lie in a trench with a little pillow to support your head while grizzled old men shovel hot sand over you till you’re completely buried apart from your face. The sand is surprisingly heavy and hot, like a blanket, and incredibly good for you, or so they tell me.

Lying on the beach, gazing at the ocean and the palm trees, I got some feeling of this beautiful place where Atsu spent her childhood and expected to live her whole life. But fate had other plans for her.

Sakurajima volcano belching black ash

Lord Nariakira’s summer villa with Sakura

At the age of seventeen she was summoned to Kagoshima, the capital of the province. As a princess she travelled by palanquin, carried on the shoulders of muscular bearers, accompanied by thousands of colourfully dressed retainers and guards and samurai and porters in a procession as vast as when the Queen travels.

Kagoshima is another tropical paradise. The great volcanic cone of Sakurajima looms over the city and the bay, perpetually belching black ash. You can see the fire spouting out of the crater at night. The town is dusted with ash and gritty underfoot and on some days you have to carry an umbrella; and occasionally the volcano erupts.

I stayed in a hot spring resort right on its slopes. These days most spa resorts have separate baths for men and women, ever since prudish Victorian travellers arrived to spoil the fun, but this one is mixed. I wore a white cotton yukata and reclined up to my neck in hot mineral waters, gazing at the sea and the sky.

Atsu was taken to live in Kagoshima Castle, the seat of her uncle, Lord Nariakira. The moat and building and vast grounds are still there directly under the lea of the hill, as are the exquisite gardens and delicate wooden tracery of his summer villa across the bay from the volcano.

From there Atsu travelled by palanquin across Kyushu to the main island, Honshu, and along what was the main highway in those days. The whole journey took her six weeks. By bullet train it took me a day.

When she finally reached Edo, now Tokyo, she travelled in a grand procession through the streets of the vast city to Edo Castle. There she entered the Women’s Palace – a harem of three thousand women, where the only man who could enter was the shogun.

Edo Castle has long since disappeared taking with it all traces of the Women’s Palace. I visited Nijo Castle in Kyoto and spent a long time in the Women’s Palace there. While the walls of the men’s palace are covered with lavish designs of pine trees and tigers painted on gold leaf screens, the women’s palace is much more restrained and tranquil in decor, with sliding doors etched with delicate ink paintings of Chinese landscapes. I walked in stocking feet around the long dark corridors past the heavy wooden pillars and beams and tried to imagine myself back to that world of women.

A version of this article was first published in Bettina Hartas Geary’s www.tripfiction.com