Atsu smelt kyara and sandalwood, musk and ambergris mingled with camphor and a dank mustiness. Glistening heads with black hair coiled into glossy loops stretched into the gloom. There were several hundred women on their knees but the room was totally silent.

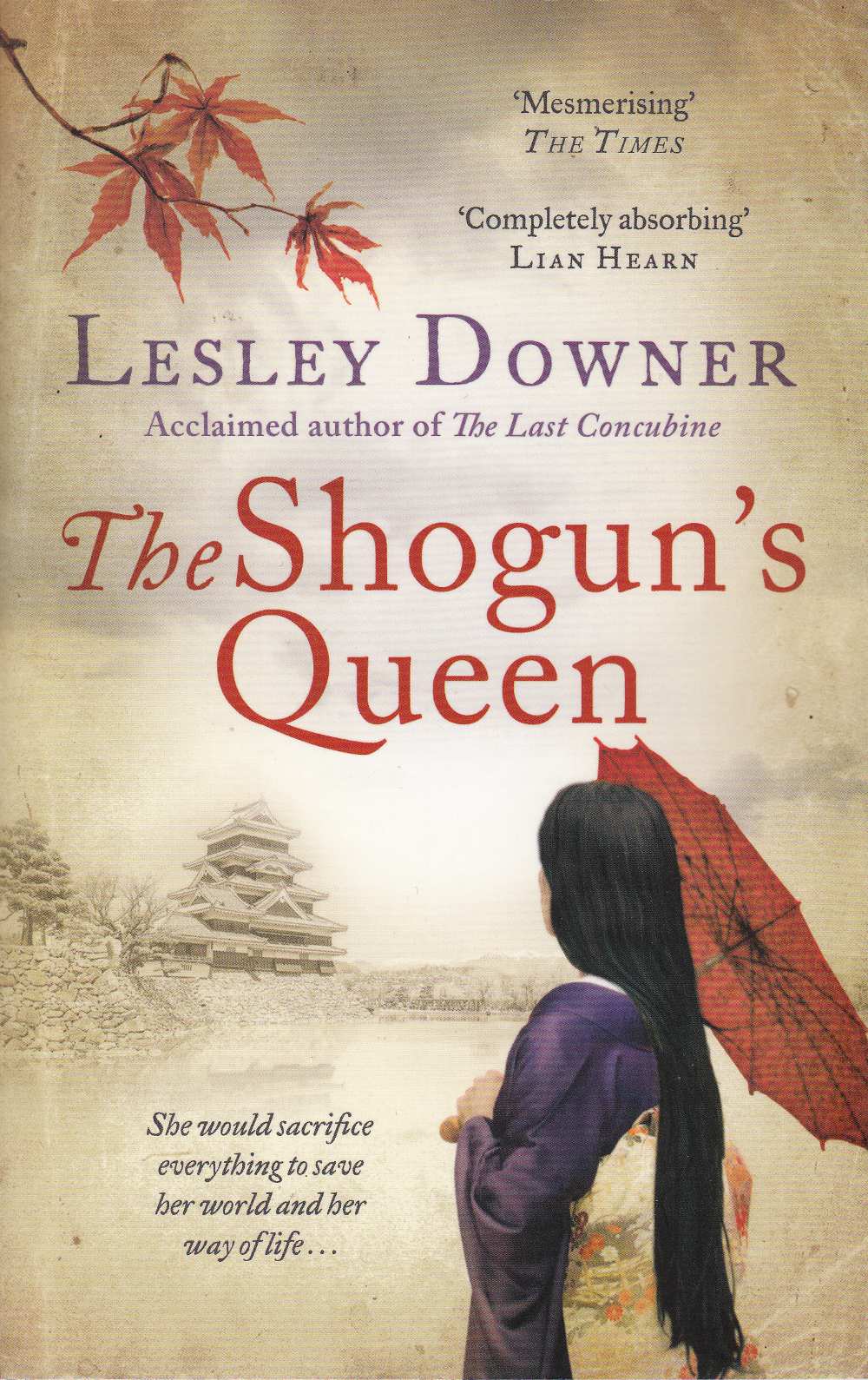

The Shogun’s Queen

In Japan until recently men and women led very separate lives and the higher you were in the social hierarchy the more separate your life was.

The Shogun’s Queen is set in a world of women in the mid nineteenth century, half way through the reign of Queen Victoria. In those days the three thousand ladies of the shogun (military governor)’s court lived confined to the Women’s Palace at Edo Castle, a vast luxurious harem, separated from the men’s palace by a solid wall. Only one man ever entered – the shogun. The women were surrounded by extraordinary luxury – richly embroidered kimonos, exquisite perfumes, delicious food. But there was also jealousy, backbiting and sometimes murder.

In my novel I tell the true story of Atsu, thrown into this claustrophobic world at the age of seventeen. The other women were all of noble birth. They’d grown up confined to their palaces. But Atsu was a commoner. Like Princess Diana or Princess Kate, she was used to freedom. Added to which she had a secret mission to accomplish in this world where everyone knew everyone else’s business and the walls were made of paper …

It was surprisingly easy to imagine myself back to that time because when I first lived in Japan in the 1980s I too lived a life very separate from men. I was one of only three westerners among a hundred thousand Japanese in the large provincial city of Gifu. I taught English in a women’s university there.

Nearly all my friends were women. We prepared meals together and took day trips into the countryside to visit ancient moss-covered temples and Shinto shrines with vermilion arches in front. I never met the husbands even of my closest friends because they were always at work.

Several of my women friends had had arranged marriages. Their theory was that westerners fall in love and then marry while Japanese marry and then fall in love. One told me laughing that she had first seen her husband’s face on her wedding day. She was perfectly happy. My friends devoted themselves to their children knowing that no matter what their husbands got up to away from home they would never divorce them. They had complete financial security.

I was single in those days and felt distinctly out of place. The women of my age were all married and they all had children. They looked at me pityingly because I didn’t have any. They got up early every day to do the cleaning; I’d hear the vacuum cleaner buzzing in the flat below mine at 6 or 7 in the morning. Every day they cooked delicious meals. And none of them seemed to know any men other than their husbands.

None of these things applied to me and I too secretly worried about why I was such an oddity.

Then, some twenty years later, I went to Kyoto, a city of beautiful ancient temples, to research a book on geisha. I found a little room to stay in in an area of narrow streets lined with dark wooden houses with lanterns swinging outside. Maiko (teenage trainee geisha) clip clopped beneath my balcony on high wooden clogs, chattering and laughing. In their gorgeously-coloured kimonos with long swinging sleeves, their white-painted faces and brilliant red lips, they were like exotic birds, more dolls than humans. But little by little I got to know the women behind the spectacular facade.

The adult geisha were, I discovered to my amazement, quite a lot like me. They were smart, canny, feisty career women, who supported themselves by their own efforts. Geisha are professionally trained singers and dancers who practice the traditional Japanese arts. None were married. None had a husband to support them. In fact geisha and wives are opposite sides of the spectrum. You can’t be both. If a geisha marries she has to give up being a geisha. Some had children but the children didn’t have visible fathers.

Unlike other Japanese women I knew, geisha got up extremely late. I never visited a geisha before 11 or 12 because they’d been out partying all night. They didn’t do any cleaning and they never cooked. They had maids to do that. And they all knew plenty of men.

In fact I fitted in perfectly. As a single liberated woman I’d found my niche in Japan.

First published in shortbookandscribes.uk.

What an interesting insight into Japan for those of us who have never been there. I always imagine it as being rather impenetrable for outsiders. Years ago a chap at work showed me a tiny black and white photo from his wallet. A Japanese woman he had been in love with; she would not leave Japan and he knew he would never be able to work and fit in so he left.